Back in Fall of 2017 I started work on Return to Sender1. This was to be a very short comic that I would incorporate into a larger set of comics as part of a personal project. I won't go into the details of that project here (perhaps another post), but instead I simply want to detail the development of what I refer to as the "top-level domain" within the comic.

Some background is perhaps in order though. Return to Sender is an idea for a short story I came up with: a visual narrative of a woman coming upon a lab not intended for her eyes, discovering tanks with brains hooked up to computers and having the startling and unnerving realization that if those brains are simulated people then she too might be simulated, and on and on. To illustrate this I intended to depict four different levels of reality: that of the woman, a lab environment above her, an industrial environment above that, and finally a seemingly alien environment as the top-level domain.

The top-level domain is intended to look strange and otherworldly. The "alien" nature of it is attested to by those who are simulating brains at this level - designated as caretakers, they are meant to be markedly non-human. This post then will cover the development of the visual look of the top-level domain - the concept - as well as the process of realizing that in the final image - the execution.

Starting Point

I started with my description of the domain as detailed in my initial story outline:

Now a giant matrix of brains in vats, connected in twisted geometric structures that seem organic and alien. It is less a warehouse of brains and more a colony of them. In the distance, sinister-looking insectoid caretakers attend to the brains with utmost care.

Concept Design

In my sketchbook I absently doodled some simple alien-like creatures working away in a computer lab-type environment, essentially combining some of the levels from the story without really thinking about it.

|

| Initial design doodle for the caretakers, here in a sterile lab environment |

|

| Design concepts for the caretakers |

|

| Design concept for the domain of the caretakers |

Further along development I decided to employ a different art style for each level of reality to distinguish them. To achieve this I wanted to employ different rendering methods as opposed to variations on the same set of techniques which would easily become hard to distinguish. Importantly, the top-level needed to be markedly distinct from the base level. I considered an escalation of rendering technique - from limited colours to full colours to fully lit with shadows - but I kept being bothered by a thought that wouldn't go away: the top-level should use photography.

I was very hesitant to commit to this path and started by trying to plan out the visual look. Solving the look of the top-level became critical since it would represent what I could not visually encroach on with the other levels.

Early Colour Studies

I did a large scale schematic sketch of the scene as it was to be portrayed which could be used either as a starting point for painting or to plan out the model-building process. I left the shapes basic in order to focus on form.

|

| Schematic sketch of the scene |

I started to get cold feet with regards to model-building and started thinking I might be able to execute the image purely as a painting. I used the schematic sketch as a basis from which to sketch a thumbnail tonal study in pencil and colour study in gouache.

With the tonal and colour studies the structures in the foreground and background became much more organic, taking a sort of coral-like appearance, with light emanating from within pockets that would house the brains. Concealing the brains in this way made the painting process simpler, as I wouldn't need to paint dozens of brains as well as a structure for arranging all of them, a task that would require careful application of perspective.

I was largely unhappy with the colour study and my attempts to manipulate the colours after the fact in Photoshop were unsatisfactory. I needed more clear direction on what the visual look of the piece would be from a colour and lighting standpoint. To that end I started gathering research materials - images and video stills - and putting together colour palettes based on these. I tried out quick variations and combinations of these palettes and decided that the image should be dominated by deep blood reds, with plumes of sulfurous yellows as accents2.

With the tonal and colour studies the structures in the foreground and background became much more organic, taking a sort of coral-like appearance, with light emanating from within pockets that would house the brains. Concealing the brains in this way made the painting process simpler, as I wouldn't need to paint dozens of brains as well as a structure for arranging all of them, a task that would require careful application of perspective.

I was largely unhappy with the colour study and my attempts to manipulate the colours after the fact in Photoshop were unsatisfactory. I needed more clear direction on what the visual look of the piece would be from a colour and lighting standpoint. To that end I started gathering research materials - images and video stills - and putting together colour palettes based on these. I tried out quick variations and combinations of these palettes and decided that the image should be dominated by deep blood reds, with plumes of sulfurous yellows as accents2.

My early attempts at painting out the scene faltered; I wanted to achieve a tactile quality to the image with believable lighting, but executing this without a strong reference proved to be too daunting.

I briefly entertained the idea of doing a 3D rendering of the scene. This would free me up from the concerns and constraints of model-building, photography and lighting, while also lending a distinctive quality that would stand apart from any painterly approaches I might employ down the line. I decided not to entertain this idea very much, as it would involve having to learn a 3D modelling and rendering program while dealing with all of the frustrations of rendering, a tall undertaking indeed3. I also felt that there should be some trend toward more physicality rather than less, as if each layer of reality is more "real" than the one beneath it. Diving into purely computer-generated imagery seemed counter to this idea.

All that deliberation aside, I took up my pen and began planning the build.

Build Planning

The first issue I needed to resolve was one of scale. I came up with some rough proportions for the caretakers based on what I felt I could model with a reasonable amount of detail using my hands. I then went through some iterations on the size of the large foreground element in the piece based on this scale. To my dismay it turned out to be quite large. Ultimately I had to fix the size of the caretakers based on the size of the brains they would be holding as going too small here would prevent me from being able to inscribe the necessary convolutions. The large tubular element in the foreground would have to wait, but it threatened to be a big undertaking.

From the scale of the caretakers as determined by the scale of the human brain model I realized that the background elements would have to be simply enormous if using the same scale. One can of course mix scales in the same shot: distant elements can be made smaller and brought closer to the camera, thus mimicking the scaling effect of perspective4. However I determined that it was not possible in my case, as I was only willing to build the background elements so large such that to contain them in the same shot would mean they interfered with the foreground models.

In order to achieve the effect of being immersed in fluid I decided to employ a cloud tank, something that I had been wanting to experiment with. A cloud tank is a term used within visual effects for film where a water tank is filmed while another fluid is dispersed within it. Within still photography the term seems to be aqueous photography, but the principle is the same. In the cloud tank setup, a layer of saltwater is set up in the tank and then a layer of fresh water is carefully set up on top of the saltwater layer, with a cover such as a large garbage bag used to separate the layers and prevent mixing during pouring which is subsequently removed. With two layers of water of different density, a third fluid (typically milk of some kind, evaporated or condensed) is introduced and floats on the denser layer, creating an effect not unlike clouds. This technique was employed in numerous films prior to the widespread adoption of CGI, including Cecile B. DeMille's The Ten Commandments (1956) and somewhat more recent fare including Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). I wasn't looking to make clouds and instead wanted simple plumes of fluid, so I would forego the saltwater layer and simply introduce milk into a tank filled with water. However, first I needed a tank and I decided to search for an old fish tank to suit this purpose.

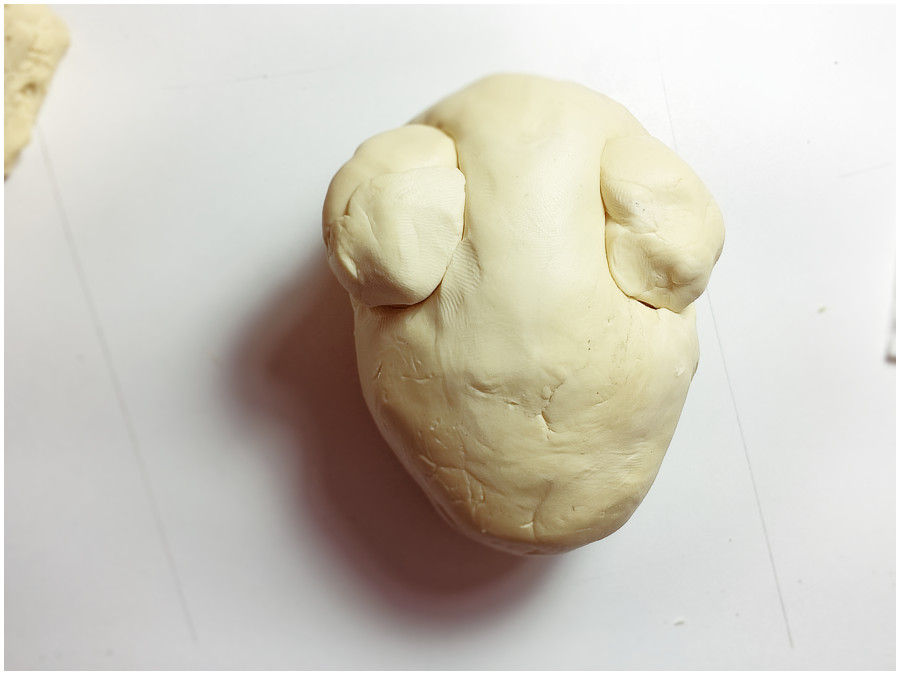

Modeling the Caretakers

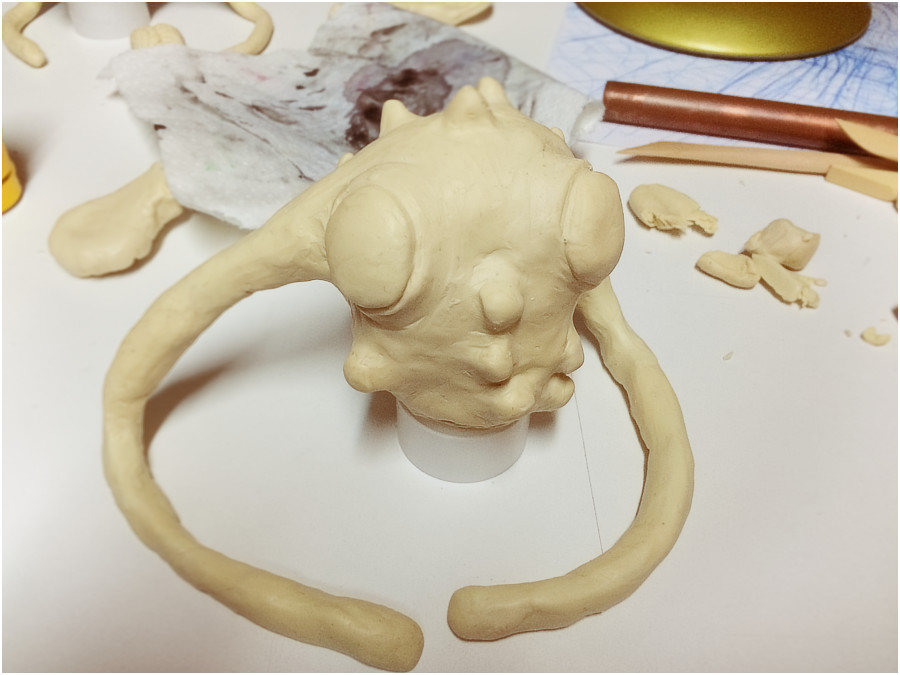

One difficulty I encountered was an unexpected hardness to the clay. The first package I used was pliable enough, but the other two took significantly more effort to work. It probably took me around two to three times as long to make the other two models as compared to the first one simply because the clay was so frustratingly hard5.

As I completed the models I ran into the issue of not having a way to prop them up - I used the inside of old Scotch tape canisters and a light bulb fixture to hold them up, but this prevented my attaching their tails. I also needed to be able to correctly position them for photography. I thought about some sort of assemblage of thin rods that would not be too obtrusive but couldn't think of what material would actually accomplish this task.

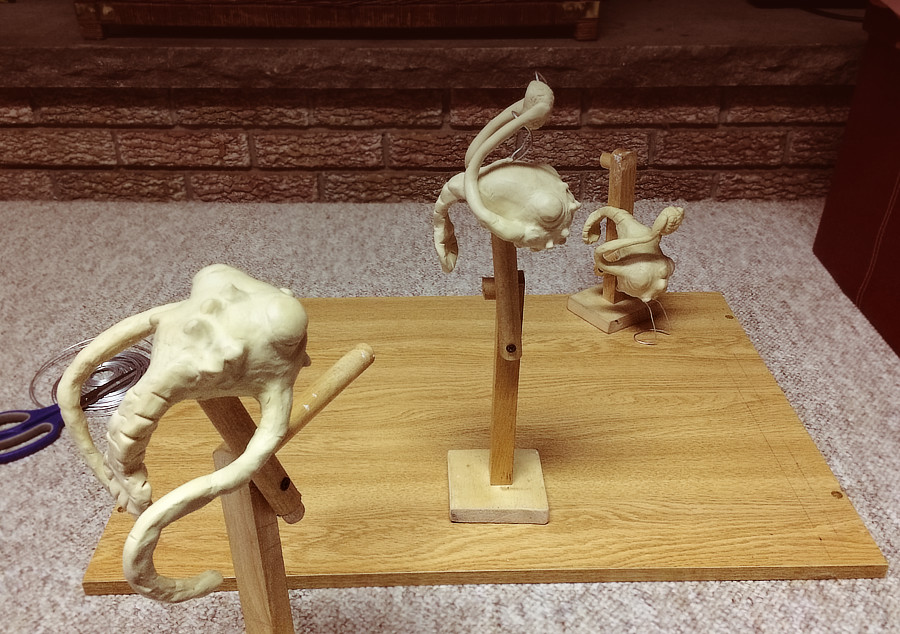

I then sketched out a design for a stand with a caretaker model attached to a fixed post with a 90-degree bend. I thought about what materials I could use here but soon alighted on the fact that I could assemble the stands from some pieces of scrap wood that I found laying about6.

A few applications of a circular saw and some screws later I had built up three wooden stands for holding the models. I affixed the models to the stands simply by making an impression into their backs and wedging the wood in there tight, folding the clay over to make a bit of a seal. There was some iteration involved in making the stands as I had to adjust them to get the positioning right for the scene; the schematic sketch was helpful in this respect.

|

| Models arranged on wooden stands |

Test Shoots and Adjustments

With the caretakers modeled and the stands built I began some test shooting and experimentation. I actually started this process while the model build was still underway, looking at ways of colouring the models in Photoshop. I had elected to use a single-colour clay for the entirety of the models, an off-white cream, in part because I did not find the alternative colours to be satisfactory, tending as they did toward bright primaries rather than more muted and realistic tones, partly because I was still quite undecided as to what colours I should use, and partly because I didn't want to end up with large amounts of unusable clay owing to it being the wrong colour. I determined that I would somehow adjust the colouring after photography.

My first pass at colouring the caretakers involved a crude application of the gradient map in Photoshop.

I later put some more effort into achieving a more believable result with the gradient map tool and found the results to be acceptable. At this point I was also incorporating an eye texture that I had painted out for the caretakers to be wrapped over top of their eyes.

One thing that my test shoots and adjustments brought to light was the need to paint the model stands. Separating the figures from the background was necessary and this could be difficult when the wood of the stands and the off-white of the clay models was so close in colour. I decided to paint the stands black as they would be against a dark background (as is typical for aqueous photography). However, I realized that I had an abundance of black ink just sitting around so I foolishly chose to paint the stands using the ink instead of comparatively scarce paint. The trouble with the ink was that it simply refused to dry, and I ended up having to heat the stands up in the oven to bake off the water in the ink, all the while being careful not to set my stands up in flames in the process.

The Cloud Tank

From the layout of the models and the test shoots I had a good idea of the rough size of enclosure that I would need. I had in my mind that I would shoot the models immersed in the cloud tank which meant the size of tank I needed was quite large, certainly exceeding what I was turning up in online searches for used tanks7.

Frustrated by my inability to find large fish tanks at reasonable prices I started to look into building my own cloud tank. With a custom-built tank I could go as large as I needed, and all I needed was some glass. To build a tank one simply needs glass of the appropriate size, a caulking gun and some silicone. If the glass needs to be cut, one can do that too using a glass cutter. All I needed was some glass and a glass cutter.

While I didn't turn up any large panes of cheap glass for use, I was reminded that there were large panes of glass stored away in the shed. Unfortunately the shed was locked and the key lost. No matter, I would cut the lock using the circular saw. However I had no extension cords long enough to enable use of the saw near the shed. After some failed attempts at breaking open the lock using the method of shims made from an aluminum can, I managed to find an old extension cord that together with the other cords lying about enabled me to use the saw. Much hacking away later and I had penetrated the lock. Finally, the promised panes of glass!

Except, they were not panes of glass, but mirrors. Sometimes knowing too much can be harmful, this was one of those times. I know that mirrors are simply glass with a special backing on one side. Therefore, if one could remove the backing - voila! - you'd be back to a regular old pane of glass. I looked it up online and found that there were indeed chemical methods for stripping mirrors. Essentially, the backing of mirrors can be removed successively through application of paint stripper and bleach, with plenty of elbow grease.

The large pane of glass I decided to use (along with two smaller panes) was 5'9" across and 3'8" wide, which should have deterred me. Instead I pressed ahead and implausibly managed to carry the sheet from the shed to the garage without breaking it.

Once inside I had a day's worth of work ahead of me. One thing to keep in mind though: the main ingredient in furniture stripper is methylene chloride which will react with bleach to form poisonous chlorine gas. I just needed to remember to thoroughly wash down the glass after using the stripper and before applying any bleach. When it came time to apply the bleach of course I forgot to rinse down the glass (although it was quite dry of the stripper at that point). As soon as I started to smell the bleach I suddenly remembered the possible danger and I became filled with dread. I felt my chest become irritated and in a panic I flooded the glass with water and rushed outside to breathe clean air. I didn't quite have a panic attack, but it took some doing for me to return to the garage (of course I opened all the windows and just left it for a good while)8.

All those harsh chemicals were not at all worth it though, the amount of mechanical scrubbing I had to put in was onerous, and I employed a power sander to get through the layers, burning through just about every scrap of sandpaper I could find lying around. Ultimately I managed to clear off the backing, at least on the main large size sheet; the two smaller panels ended up being remarkably stubborn, having an apparently slightly different backing. I moved the glass to a table and marked out where I needed to cut it. Which brings me to glass cutting.

One can cut glass using a glass cutter which is simply a small rotary cutting tool that scribes the glass. The glass then needs to be held over an edge and forcibly bent along the scribe line, causing it to snap cleanly off. If that sounds like it won't work, you're right, it doesn't. With the size of my panel there was no way I was going to be able to hold it over an edge and apply even leverage across the entirety of that edge. I did manage to cut the panel, although I lost a large chunk in the process which promptly shattered. However I ended up with crooked edges that gave me smaller panel sizes than I needed. More than that, the cumbersome, imprecise and frankly ridiculous process of glass cutting completely turned me off from trying to salvage this disastrous project.

Defeated in my attempt at building a fish tank I began scouring the local thrift stores for anything suitable. I expanded my search to contain essentially any clear container I could think of, including something made of plastic, so long as it was fit for purpose, but I was unable to turn up anything of use. At this point I had given up on the idea of shooting the models in the tank, opting instead to composite them together after the fact. This freed me up to consider any size tank I wanted so long as it was large enough to cover the field of view. Even so, my searching was unsuccessful9.

Eventually I learned of a local Sunday flea market, where I was told a woman sold fish tanks among other things. A visit to the market did not disappoint. While only one fish tank was there and it was perhaps a little on the small side, the price ($5) was well in-line with what I was looking for so I was happy to take it.

Setting Up the Environment

With a fish tank acquired I set up a space in the laundry room to conduct my shoot. Importantly I had easy access to a tap and sink which I could use to fill and drain the tank. I found some old hoses to affix to the tap so that I could fill the tank, however, there was no secure fit between hose and tap. Not about to spend money on a hose attachment, I tried various attachment methods, including cutting a balloon and taping it to seal the gap from hose to tap. In the end I found all of these methods to be worthless and obtained the best results with a small diameter hose that I simply shoved up the tap. While there was some leaking between tap and hose, it remained quite tolerable.

I used an old tool chest as a stand for the fish tank and created a black surface on its top by taping letter-sized sheets of black construction paper to it. I found a large panel of poster-board which I similarly covered in black construction paper and used it as the backdrop for the tank. I then used the hard backing of some old sketchbooks covered in black paper as the sides, thus enclosing the tank in a black environment.

With the tank set up it was time to test out filling it up and shooting it. Filling up the tank went easily enough. When it came time to drain the tank I simply submerged the hose in the tank and turned on the tap until it was filled with water, I then turned off the tap and disconnected the "tank" hose from the "tap" hose and lowered the end into the sink. Fortunately the sink was a little lower than the tank, making this siphoning possible10.

Around this time I also began experimenting with different fluids. I used red and yellow food colouring and tried various combinations of them with water and evaporated milk. I found that good contrast was only obtained for the non-coloured milk in water, with the yellow unable to contribute much. The red colouring seemed to work, although it made visibility of the milk more difficult. I didn't really come to any conclusive decisions from this experimentation.

|

| Red and yellow food colouring tests |

Shooting

Since I had committed to a photoshoot, you'd think that I had a camera with which to pull it all off, however my only cameras are an old film Pentax KX with a broken light sensor and my iPhone 5S. Trying to work with film was out of the question; the shoots would be particularly light-sensitive and need real-time adjustments, I wasn't about to take ages going back and forth developing film to figure out acceptable lighting and camera settings. With the iPhone I didn't feel I could capture images that would hold up in print with its camera. So I resolved to renting a camera.

Renting a camera turned out to be problematic. As it happens the only place nearby that rents cameras is Vistek in Ottawa. They are quite high-end and don't offer anything for the considerable gap between an ancient iPhone and professional gear. Their cheapest offerings were hundreds of dollars a day for a rental. Beginning to despair, I turned back to my iPhone and began looking at photo apps as alternatives to the default app. My initial enthusiasm was dampened as I realized that the 5S is unable to save RAW images and my results with different apps were unable to get acceptable quality. In the end I was able to borrow an old camera and tripod from my sister, a Fujifilm FinePix 5200 from 2005.

For the comic I had decided on a B5 page size format, the dimensions of which are 176 x 250 mm. For the double page spread my dimensions would be 353 x 250 mm (B4 size) and for print quality it would need to be at 300 dpi. This gives an image size of 4169 x 2953 pixels (around 12 MP), quite a bit larger than the 5 MP pixel images I was able to get out of the FinePix (for comparison the iPhone 5S is 8 MP as compared to 5 MP for the FinePix). I didn't put too much thought at the start of shooting as to how I would bridge the gap between what the camera could capture and my final image requirements11, however I found the FinePix to be preferable to the iPhone since I had an existing tripod for it whereas for the iPhone I would need to buy some sort of mount and the FinePix offered greater control and ease of use while also enabling me to save RAW images. I found the RAW images preferable to the heavily processed images from the iPhone.

With the camera and tripod I still thought I might rent some lights, but I decided to see how far I could get with what I could find, as again the prices seemed rather extravagant. After some experimentation I settled on using some LED flashlights that I was able to find lying around. I used some sheet music stands that were stored in the basement as adjustable stands for positioning the lights. One of the lights had a magnetic base so I was able to stick it to the metal stand and then adjust until I got an acceptable angle and coverage.

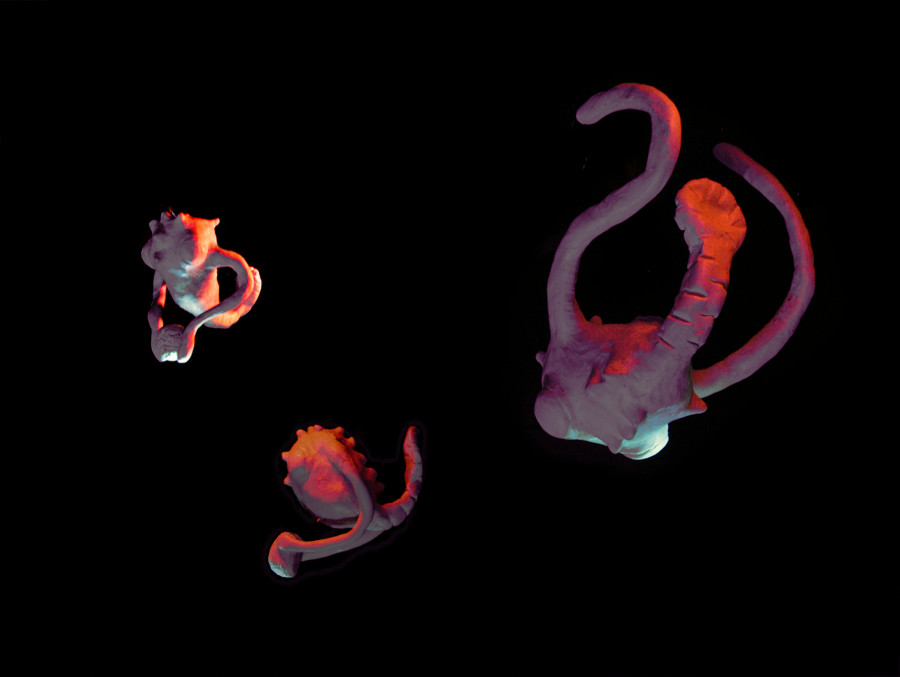

While my early colour replacement studies produced some usable results, I did not get to the point of getting convincing coloured lighting. Further research led me to conclude that it would always be best to start with the colour information that was needed, as adding it afterward was cumbersome and unconvincing. To colourize my lights I went out and bought a pack of clear coloured plastic folder separators (just $1.57 for an 8-pack) and then cut them to size and taped them onto the flashlights. I was pleasantly surprised to discover that the effect worked rather well so long as the sheets were doubled up. I found I could get the best results from the red and blue sheets and decided to use this as my colour scheme. I knew that I could adjust the colours after the fact, and a stark contrast between the colours would work better than two colours that tended to wash into one another.

I lit and shot each of the models independently. This was to compensate for my shortage of lights and stands. Ideally I would have lit them all with singular light sources bright enough to illuminate the entire scene. I shot them all from the same fixed point of view, not wanting to introduce more artifice than was necessary.

After shooting the models I moved on to shooting the background using the cloud tank. Here I started by trying out illuminating the tank with my red lights and found the results to be such that I saw no reason to use the food colouring. It was difficult to get clean usable images and I would have really benefited here from more professional lighting, but I was able to make do. I got plenty of coverage under red, blue and white lighting conditions12.

I hadn't made any progress on the structures in the scene and had resigned myself to the idea of painting them in. However one thing that became clear to me from the shoots was that it was much more about form and lighting than it was about details. If I could find a suitable tubular form it could serve as the basis for further painting. I ended up finding a vacuum hose which I twisted in various positions while shining light on it. The intent here was initially to provide some lighting conditions similar to what was on the models, but the way the tube caught the light gave the fortuitous impression that the lights were coming from the tube itself.

Compositing the Image

I needed to do composites hand-in-hand with the photography in order to know if what I was shooting was going to work out. To that end I started making mock-ups before I had even started the shoot proper, when I was still simply snapping images with my iPhone.

In the early stages I simply took an image of the models fully lit and attempted to adjust their colours in Photoshop. It was this early experimentation which led me to use coloured lighting in the photography rather than trying to incorporate it in post.

While I had determined to shoot the models with a combination of red and blue lighting, I didn't know what combination of lighting conditions would work out. I took advantage of the fact that I was photographing still models and took multiple images under different lighting conditions, enabling me to experiment with different combinations in post. The key advantage this introduced was being able to capture much more detail in the shadows by layering it in from brighter lighting conditions. The main disadvantage was simply that I ended up with a plethora of possibilities to experiment with: direct lighting, indirect lighting, indirect lighting plus the red and blue lights, illumination from the red and blue lights alone, and the red and blue lights considered independently. My experience here was that it is best to capture as much as possible in a single shot, with the layering approach valuable insofar only as it was able to compensate for the limitations of my camera and the very dim lights that I was using.

Once I had reasonably acceptable compositions for the models I moved on to the background. Here I ran into the problem of low resolution. While the figures occupy only a small portion of the page, the background encompasses its entirety, so it must be a 12 MP image. Trying to stretch the image and salvage the quality in post was not at all promising so I took several different shots of the tank and stitched them together, forming a kind of panorama. I then had to paint over this so as to cover the seams between the images and to provide vertical extension.

I layered in the tubes, using mesh warp to get them into the positions that I wanted. There was iteration here between shooting the tube and compositing the image as I experimented with different orientations and tried to match a laid-out plan. For the distant background tubes I realized it was simply far easier to go with a pure painting approach. I ended up deviating significantly from the initial layout sketches here as I responded to the elements that were in play.

|

| Iterative progression of the final image |

|

| Layered breakdown of the final image |

The main challenge I encountered in putting together the image was lag and program crashes. I was using Affinity Photo for this as I no longer had a Photoshop license13 and every small change was met with agonizing periods of waiting.

Conclusions

Overall I'm satisfied with the image, although I don't know that I consider it final at this point; there is perhaps more work to be done to convincingly depict it as immersed in fluid. I think it succeeds in establishing a visual look that will immediately read as distinct within the frame of the narrative. The red/blue lighting scheme does seem to have a certain classic science fiction or Terminator 2 vibe to it and I remain undecided as to whether I will adjust the blue further; it does fulfill a role of providing a recognizably technological aspect to the more organic environment.

Despite some difficulties with the clay, the modeling process was largely enjoyable and the resulting surfaces provide lots of opportunity for interesting captures of light. I would like to incorporate more model-building into my illustration, but it does bring with it certain cost and space constraints. I think avoiding building any elaborate structures was the right choice here, it's simply way more ambition than is called for. Here however I do see an opportunity for 3D modeling and this is an avenue I may pursue in future projects.

The shoot was not without difficulty. The FinePix devours batteries which introduced numerous interruptions into the shoots. Perhaps the biggest difficulty though was setting up the lights, with the music stands just barely sufficing. I feel that any future attempts at photography on my part will require my having a decent camera as a starting point. I think with a decent camera it would also be easier to justify renting suitable lighting.

The key frustration with models is all the practical considerations that seem to only be of secondary importance to the final image: how to hold and position the models, how to position the lights, etc. However this is offset somewhat by the opportunities for serendipity. Ideas can be discovered in an exploratory process that involves working with the material; the materiality of the clay informed the shape of the caretakers more than any elaborate planning would have which then informed the positioning of the lights in the shoot. After struggling through compositing the final digital image, the immediacy of response of working practically is not to be discounted either.

Footnotes

1 My work on the project has been intermittent to say the least, with there often being long stretches of time between very short bursts of productivity as a consequence of other obligations.↩

2 My decision to go for reds was not arbitrary. The otherworldly is typically represented by cooler hues - blues, greens, purples - and I wanted to get away from this overused convention. But my thinking was also that the red suggested something amniotic, womb-like, and internal. Since this is the outermost layer it seemed appropriate that it should connect to the innermost and go back to origins. By contrast I didn't have much justification for the yellow, simply that I didn't want an entirely monochromatic look and thought this combination might work.↩

3 Part of what makes practical effects appealing is the number of things one gets essentially for free; in my case lighting and fluid behaviour, both computationally very expensive and difficult but achieved relatively easily with practical models.↩

4 This is a technique that was familiar to the visual effects film industry prior to the domination of CGI. Shots such as the opening city-scape in Blade Runner (1982) were accomplished using models of decreasing scale arranged before the camera.↩

5 As an aside I did try warming up some of the clay using a microwave but this simply dried out the clay, making it crumbly without appreciably improving the malleability. I had slightly better results setting the clay under the radiant glow of an incandescent bulb to warm it up.↩

6 I ended up cannibalizing the remains of an old broken table which I had also used to make a bookpress for another project (see here).↩

7 Even with such a large footprint, I realized that it seemed unlikely I would be able to fit the foreground tube in the tank. As well, the models were to be shot upside down, so that shooting them with the tube would introduce the further complication of needing to construct the tube affixed to a surface in such a way that it could be placed upside down over top of the tank. For these reasons I didn't let the foreground tube influence the size of tank I had in mind.↩

8 In hindsight I likely overreacted a good deal, chlorine gas is poisonous but not instantly lethal, and given that it is yellow-green in colour in all probability I didn't make any of it. I think my reaction was purely to the bleach and then my fear likely triggered some kind of psychosomatic response.↩

9 I did consider using stock imagery and did some early experimentation in this direction, however I was put off by the tyranny of choice that awaited me in that direction - there are seemingly infinite options, yet none will yield to one's specifications. I put this down as an option of last resort.↩

10 I should note though that I wasn't able to get all of the water this way and the siphoning typically failed leaving about a quarter of an inch of water still in the tank. In the worst case I was left with perhaps an inch of water. At this point I was able to lift the tank and empty it into the sink, so it wasn't a problem for me, but a much larger tank could be a different story.↩

11 It was an understanding of the resolution requirements that had motivated my initial intention to rent a camera.↩

12 For the white lighting I used one of the same flashlights, replacing the plastic red cover that I had made for a diffuser made of cut sheets of wax paper that were taped together.↩

13 To be fair I don't know that Photoshop would have proved more stable and less lag-prone for the image, although my previous experiences compositing large images using it seem to suggest this.↩

References

Blade Runner (1982) Directed by Ridley Scott [Film]. Burbank, Calif: Warner Bros. Pictures.

Corporals Corner (2017). How To Open A Padlock Without A Key. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=slFmyDCZP28 (Accessed: 22 January 2019).

DoItYourself.com (no date) How to Remove Backing Paint on a Mirror. Available at: https://www.doityourself.com/stry/how-to-drill-into-plexiglass (Accessed: 22 January 2019)

Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) Directed by Steven Spielberg [Film]. Hollywood, Calif: Paramount Pictures Corporation.

Remove Silver Backing From a Mirror (To Clear Glass, Not an Antique Mirror Instructable) (2018) Available at: https://www.instructables.com/id/Remove-Silver-Backing-from-a-Mirror-To-clear-glas/ (Accessed: 22 January 2019)

Shanks FX (2015). Cloud Tank Creation | Shanks FX | PBS Digital Studios. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-qou5sDOO8k (Accessed: 22 January 2019)

Shanks FX (2015). Cloud Tank Magic | Shanks FX | PBS Digital Studios. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RypKl8MJPRE (Accessed: 22 January 2019)

Square Mountain (2018). Create Amazing Photos Using Milk | Aqueous Photography Tutorial. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4L3KCHHAu6Y (Accessed: 22 January 2019)

Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) Directed by James Cameron [Film]. Culver City, Calif: TriStar Pictures, Inc.

The Ten Commandments (1956) Directed by Cecile B. DeMille [Film]. Hollywood, Calif: Paramount Pictures Corporation.