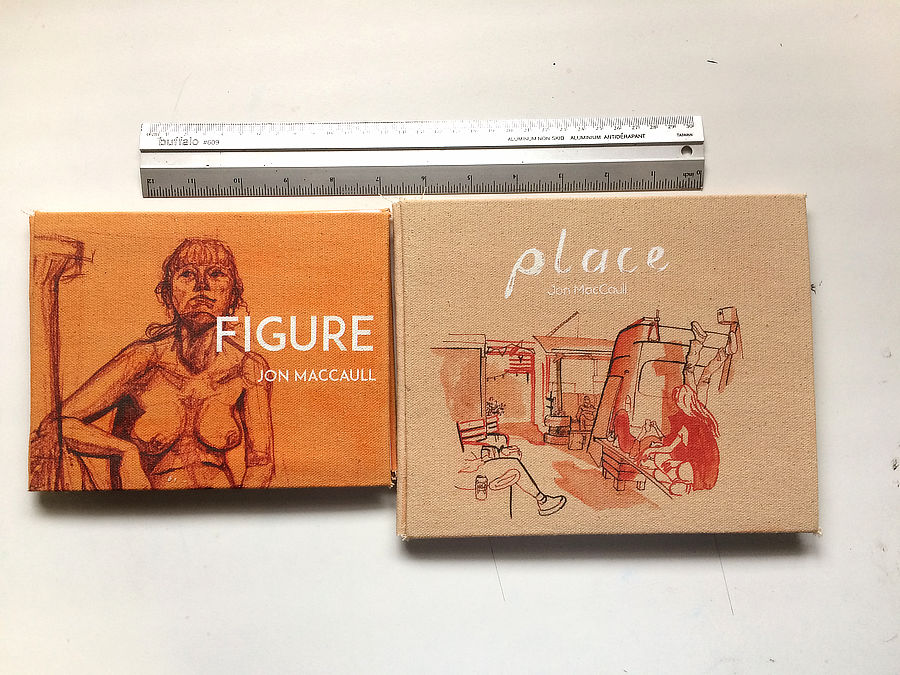

Having successfully completed several process/art books for my assessment in spring (here), I decided to follow-up two of those books with more complete ones. One book was a collection of watercolour and ink location sketches, and since my assessment I completed several more sketches that I wanted to add to the set. The other was a collection of my life drawing sketches, but only covered the period of concern for my assessment, and not wanting to leave my earlier life drawings stranded, I felt that incorporating the bulk of them into one book would be desirable.

In addition there were a number of issues with my previous books that I wanted to correct. For one the stitching was poorly done as I was very new to the process, in a rush to get them done at that point, and using a much too fine string (although I didn't know it at the time). The end result was that the books were loosely bound and would unsatisfactorily slide around in the hand. The books felt always on the verge of falling apart. The other problems included slight page alignment errors (front and back printing) and the vertical misalignment of a few pages in the figure drawing book. New books then would correct these errors, bringing forth more complete and less error-filled revisions.

Little did I know what difficulties I would encounter on the way...

What I foresaw as simple updates turned into a nightmare of frustrations. In part this was due to my ambitions growing too large, but it was also largely the fault of being removed from resources and placed into a situation with such abysmal resources at hand that calling them as such seems an affront to the term.

I started work on the new books while I was still in the UK, scanning and adjusting the remaining sketches and putting the books together in InDesign. My expanded ambitions involved large format books of unconventional size and fully printed covers. For the original books I had used non-printed covers of textured coloured paper with letterpress titles put into place. I knew that I wouldn't have access to letterpress facilities for the new books, so the printed covers also became somewhat necessary. With the books designed I headed back to Canada with the intent to realise them in physical form there.

The large-scale format immediately became a problem. The binding method I had used in my previous books and planned to use for these ones involved folding the pages and sewing them together. This effectively requires that each sheet of paper be twice as wide as the final intended page size. With wide pages, the sheets needed to become quite wide indeed, and finding capability to print on them is difficult. After searching high and low I found that my only option for printing at that size was on 24" printers generally used for high quality art prints. As well as being very expensive, such printing is not typically used for front and back-sided printing, so that introduced another complication.

Prototyping

Unlike with my process books, the formats I had decided on were not based on any existing books that I had in hand. I determined what size I wanted them to be by sketching them out, but I foolishly neglected to prototype this size. At a loss for how I was going to print the books, I decided to engage in making a prototype for the most unconventional of the books. Doing so revealed a glaring oversight: owing to the aspect ratio, the book would require a robust hinge mechanism that I had not anticipated.

I had also used my prototype to try out an alternative binding method: perfect binding. In this method the pages are not folded, rather single sheets are stacked together and simply glued along the edges. Switching to a single sheet binding method would enable me to print the books much more affordably without compromising the format. However, I found this binding method to be weak and unsatisfactory. Combined with the complications arising from the need for a hinge mechanism, I was no longer devoted to the originally envisioned book formats.

Already feeling that too much time had been invested in this project, I resolved to redesign the books to more conventional formats. While I was at it I would shrink them down to fit onto the page sizes that I could get printed without jumping to an expensive 24" roll.

Typography

For the location sketch book I had a title not only for the first page and cover, but also to denote the separate locations of Barcelona and London into which the book was divided. For these titles I was never really satisfied with the fonts that I tried out and decided that they needed to echo in some way the sketches themselves. The neo-grotesque fonts I had tried out were not producing the kind of contrast I had intended against the images.

Rather than spend a lot of time searching for the right kind of hand-written font, I simply went about writing the titles out myself. I used my Pentel brush pen and simply wrote out roughly what I was looking for on some grid paper with ruled lines. Writing out and then scanning text was a technique I had used earlier in the year on a course project after much time was spent trying to source a suitable font to accompany the illustrations. I scanned in the text, did a minimum of cleaning up in Photoshop, and simply placed the titles in as images.

The brush pen is a tool that I used in my sketches for the thicker lines, so it echoes rather than contrasts with the illustrations. However, the titles do contrast against the backgrounds on which they are placed, which consist of highly geometric map data of the respective cities. In hindsight, it was perhaps these backgrounds which was making my initial font selections appear so ill-suited. Much in the way that I did the sketches, I did not overly invest in thinking about the letters, being careful but not obsessive, while trying to get the brushstrokes to come through.

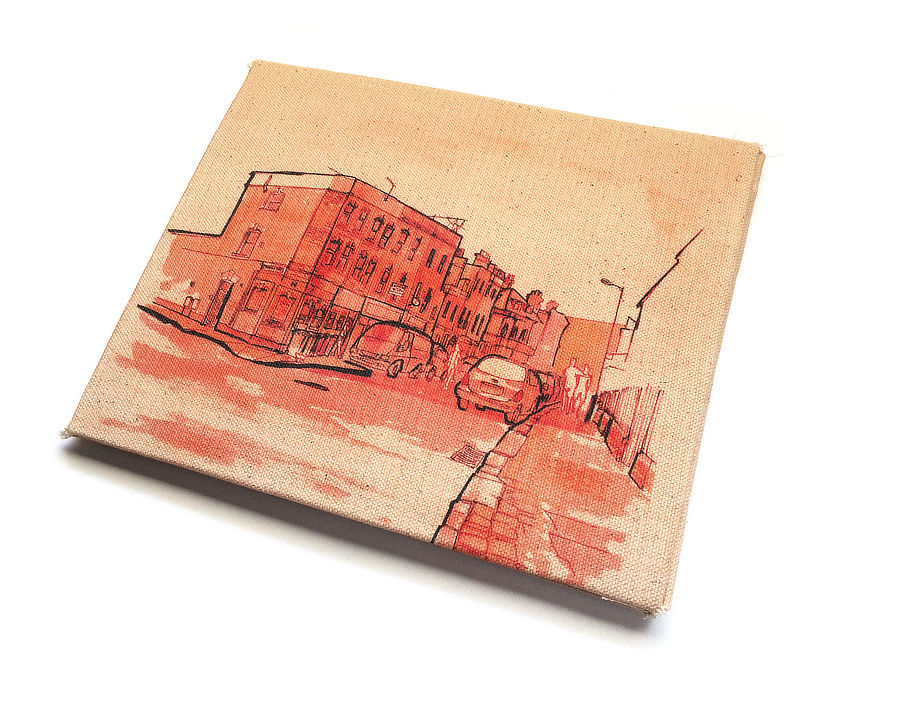

Covers

For the covers I needed some hard board that I could use as a backing. In the UK I had simply used the backing of old sketchpads or the board that came with paper samples. I found greyboard (or chipboard as it tends to be called in Canada) difficult to come by, particularly in sizes large enough for my needs. Most of the sketchpads as well seem to use a much thinner and flimsier backing than what you find in the UK, making that option not workable. In the end I did end up going with the backing of a sketchpad though as the alternative would have required ordering a large pack of board online at considerable expense, and while I reasoned that it should be sturdy enough to support the glue, this proved not to be the case.

Unlike with my process books, I wasn't going to use card paper for the covers, since I wanted to have a printed design on them. I looked into different bookbinding cover materials (namely vinyl and buckram) and at different printing processes that were available for them. I decided to buy some cotton fabric similar to buckram from a fabric store and try out printing on it.

For printing, I simply taped the fabric onto a sheet of paper so as to restrict any frayed edges and put it through an inkjet printer. To my surprise it worked out, and while not doing a great job, given the seeming expense of alternatives I elected to stick with it.

I prepared the cotton by first cutting the sheets to the appropriate size and then ironing them flat. Once ironed I taped them down and printed them out. After printing I realized my first issue: the titles as I had designed them were in white, but the fabric itself was substantially off-white, so that clearly distinguishing the title from the background was not that easy. On a test sheet I experimented with applying some white acrylic paint to the fabric to fill in the title and found the result satisfactory. I then proceeded to very carefully paint in the titles on the printed covers.

Once the covers were dry I realized my second issue: one of the sheets was too small to wrap over the cover on both sides. I had trimmed the sheets so that I could tape them down to a letter-size sheet, but I needed nearly the full width of a letter-size sheet to get sufficient wrap-around. After some trials I opted to just put a sheet of cotton into the printer without taping it down to any paper. After jamming on the first try I was able to coax it through on a second attempt. With the new front and back covers for one book printed, I went about painting in the title again, now on the new cover.

Once the cotton was painted and dry, I set about gluing them onto the board. I applied the glue using a brush to give an even coating and to avoid over-saturating the board. After gluing on the fabric I put the covers into my homemade bookpress, which enables me to apply a significant and even amount of pressure for as long as necessary. I made the bookpress in anticipation of this project using wood for some old broken tables that were lying around.

Unfortunately, despite becoming rather flat after prolonged time in the bookpress, the covers exhibited a tendency to drift into a concave shape over time; the backing material is simply too flimsy to withstand the glue.

Printing

Having redesigned my books to fit within the confines of what I could get cheaply printed, I thought my printing woes were over. However, the print shop I went to use did not have any matte paper in the size I wanted, so I would need to supply my own paper. After some head scratching and looking around for a paper supplier, I decided to be as simple as possible and simply purchased an art pad with the paper size I needed. Unable to get the right size, I had to settle for a pad where one sheet would need to be cut to get two sheets. All I needed to do was remove the paper from the pad and cut it in half, simple right?

First there's removing the pages. In the pad they were perforated sheets, which is supposed to make for easy removal but in practice makes for a nightmare. The perforations are inconsistent, so that while one sheet will pull off cleanly, the next will get stubbornly stuck along the way, often tearing and ruining the sheet. Close inspection revealed that for the majority of the sheets the perforations do not consistently go through the sheet, often becoming so faint as to be barely visible. I found the only consistent way to remove the sheets was to carefully employ a pair of scissors to cut along the perforated edge.

Next the sheets needed to be cut. The print shop did not have a big enough paper cutter for the sheet sizes, and while the local office supply was able to cut the sheets, they quoted me $15 for cutting them all, which frankly is just too much for cutting a few sheets in half. Having no paper cutter of my own, I set about carefully cutting each sheet with a straight-edge knife and ruler. It was a time-consuming and trying task, and the end result is less than spectacular, with the edges lacking the crispness one gets from a good guillotine.

Paper removed and cut, I took them over to the print shop to do a test run. Being wary of alignment and colour reproduction issues, I wanted to iron out any bugs first before going ahead with a full print. The first print showed significant front-to-back alignment issues, but I was assured that this could be worked out. I waited to hear back how the alignment trials went and put it aside.

The printer fixed the alignment issue and informed me that all of my pages had been printed - all of the test page. This was of course not what I wanted and meant all of my paper was wasted. Frustrated, I decided not to deal further with this print shop and sought out another one. Now I was told that I needed to use the print shop supplied paper. While they didn't have any matte paper on hand, they said they were able to order it and assured me that front-to-back alignment would not be a problem.

The second printing was less fraught with problems, but by this point I had essentially given up on the project; it had simply consumed too much time and mental energy for what it was, none of it really focused on making a better end result but instead on logistical issues. The printed result was well aligned front-to-back, but to my dismay it was on a glossy stock paper that was too light and the colours were unfavourably hue-shifted towards yellow. For the most part I didn't really notice these issues until I got the pages back, laid them out and did a proper assessment on my own. I decided to go ahead with making the books, since I just wanted to wrap things up at this point: if I really wanted to realise these books properly, I was going to have to start over anyway.

Cutting and Binding

The printed sheets still needed to be cut to size. Again I was resigned to use my straight-edge to make the cuts, which simply reinforced to me that the process of book-making is an utterly futile endeavour without a proper guillotine.

With the sheets cut I folded them over and used the bone folder to get crisp edges, then nested them into signatures. I marked out the positions where I wanted the holes on the top signature, then stacked them in order and marked the sides where those positions where. Using an awl I made holes in each of the signatures where I had marked. I sewed the signatures together, and thanks to my experience with making sketchbooks the process went significantly better than on my process books.

With the signatures all sewn together, I put them into the bookpress and then glued the spine. I had tried this technique before and found it to work fairly well. I let the spine dry and then applied another coat of glue. After that dried I pulled the textblock out of the bookpress and glued cover pages to the front and back pages; these pages would glue to the inside covers of the book. I then glued a sheet of paper around the spine and put the whole textblock back into the bookpress.

With the textblocks completed I arranged them between the covers to roughly size out the thickness of the books. I cut some cotton fabric strips to conceal the spine and glued them between the covers. I then glued the textblocks into place. When I made my process books in May I discovered that I needed to use a different glue for the inside covers to avoid buckling. This is a lesson that I had evidently forgotten, perhaps in part because I had since run out of any other kind of glue and switched to brushing the glue on, and while I used a heavier paper stock than that used throughout the books, it still proved not very capable of holding up against developing some wrinkles. I put the books into the bookpress and let them sit overnight.

Coming back to the books I was disappointed to find that the thin inner pages had taken on wrinkles that had seemingly propagated through from the inside covers. In fact the pressure had minimized the wrinkles on the inside covers to a tolerable amount but displaced it onto the thinner stock inner paper so that the entirety of the two books were now ruined.

With the books refusing to remain flat, bending more with increasing time out of the bookpress, they are not even usable as paperweights.

Final Outcomes

Conclusion

While my first attempt at bookmaking had its fair share of frustrations, I came away from that experience largely positive about bookmaking, sure that I could improve my skill, making bookmaking a useful endeavour. My experiences remaking two of those books have completely soured my opinion of the whole process. I see much more clearly now that any attempt at making is entirely contingent upon having a set of known resources at hand. No book format can be adequately decided without knowing what printing sizes are available in advance, sizes that may prove so restrictive as to quell the motivation for the whole project. Paper selection cannot be made without the printer being known, since the printer may disallow the use of custom paper, and the printer will dictate the paper size. The printer should be equipped and prepared to cut the pages down to size, as taking this on without a proper guillotine cannot accomplish a satisfactory quality of cut. Printers are also notoriously error-prone, so lots of trials should be requested up front to prove out that the process will provide the desired results.

Of course many of the pitfalls I encountered could have been avoided had I properly prepared. I unreasonably took my prior bookmaking experience to be a form of preparation, despite the conditions (available resources) that made that process possible having completely changed for me. First there is the need to prototype the book format; this wasn't apparent for my first books since I was working off existing designs, but changing the parameters requires revalidation. Working with the actual printing paper is also necessary to anticipate any potential issues that might crop up in the binding process. Then there is the need to consult and consider the variety of binding methods available. I was unprepared to learn a new binding method for this project and stuck with a technique that I had evolved from my earlier books; while I briefly considered reconceiving the books as screw-post bound books, this expanded the scope beyond what I was comfortable committing to, although it may have been better for the books in the end. Ultimately a host of specialized equipment and knowledge is needed to make books of decent quality, suggesting that the entire process be left to an expert. This leads me to the disappointing conclusion that one-off prototype bookmaking is a waste of time: I don't recommend it.